Best Management Practices on Indiana’s State Forests

Starting in the early-1990s, the Indiana Division of Forestry (DoF) worked with the Woodland Steward, private woodland owners, non-government organizations, and many state and federal government agencies to develop the voluntary Indiana Forestry Best Management Practices (BMP) program. In the mid-1990s the BMP Field Guide and the BMP Monitoring form were completed, and the first round of BMP monitoring was carried out in 1996 on mostly private timber harvests in the eight counties that the Lake Monroe watershed touches. By 1999 the BMP program was firing on all cylinders with a cost share program and monitoring being carried out all over the state. During this time, it was decided that BMPs would become a contractual obligation on state forest timber sales and at the close of those harvests every harvest area would be monitored to see how well they were completed during the harvest. Work to prepare the state forest system went on for years and was implemented July 1, 1999.

Unlike some states, Indiana’s BMP program was set up to be voluntary, but the state forest program decided to implement contractual obligations to be sure BMPs were carried out to a consistent level. The state forest program could be a model for landowners; however, it did not mean the state was making people go back and closeout whole trails because one waterbar was not within the recommended distances for the slope of that trail.  It meant diversions were placed such that the resulting erosion was held to a minimum and that the goal of minimizing the harvest’s impact on water quality was carried out successfully over the long term. “Long-term” meaning that it not only diverted the water but also kept the trail from washing out over the 20-year period. The state forest BMP program can show its success through the results of the BMP monitoring of those sites. In essence, the foresters and monitors look at each site for the BMP practices used or not used, but they are not breaking out tape measures to be sure every BMP practice meets the BMP guidelines to the letter.

It meant diversions were placed such that the resulting erosion was held to a minimum and that the goal of minimizing the harvest’s impact on water quality was carried out successfully over the long term. “Long-term” meaning that it not only diverted the water but also kept the trail from washing out over the 20-year period. The state forest BMP program can show its success through the results of the BMP monitoring of those sites. In essence, the foresters and monitors look at each site for the BMP practices used or not used, but they are not breaking out tape measures to be sure every BMP practice meets the BMP guidelines to the letter.

To know what the state is enforcing from that contractual obligation all one need do is look at the BMP Field Guide, which was originally written in 1996, revised in 2005, and it is currently undergoing another revision. The revisions make technical changes to only a small number of things, updates contact information and sources of materials, and refresh the format. However, most of the guidelines remain the same. The current BMP Field Guide, 2005 edition, can be found at https://www.in.gov/dnr/forestry/files/fo-2005_Forestry_BMP_Field_Guide.pdf. These BMPs are enforced to the best of our abilities and in the most consistent manner possible by multiple professionals in the field across varying topography, and geology. Consultant foresters and landowners have begun to include BMPs in their timber sale notices and contracts but are enforced to a much broader variation than state forest timber sales, which is a step in the right direction. Also, timber harvesting professionals (loggers) have taken some of the practices they have been doing on the state forest and starting to practice them to varying degrees on private land, which is also a step in the right direction. But only the first step of the journey.

To know what the state is enforcing from that contractual obligation all one need do is look at the BMP Field Guide, which was originally written in 1996, revised in 2005, and it is currently undergoing another revision. The revisions make technical changes to only a small number of things, updates contact information and sources of materials, and refresh the format. However, most of the guidelines remain the same. The current BMP Field Guide, 2005 edition, can be found at https://www.in.gov/dnr/forestry/files/fo-2005_Forestry_BMP_Field_Guide.pdf. These BMPs are enforced to the best of our abilities and in the most consistent manner possible by multiple professionals in the field across varying topography, and geology. Consultant foresters and landowners have begun to include BMPs in their timber sale notices and contracts but are enforced to a much broader variation than state forest timber sales, which is a step in the right direction. Also, timber harvesting professionals (loggers) have taken some of the practices they have been doing on the state forest and starting to practice them to varying degrees on private land, which is also a step in the right direction. But only the first step of the journey.

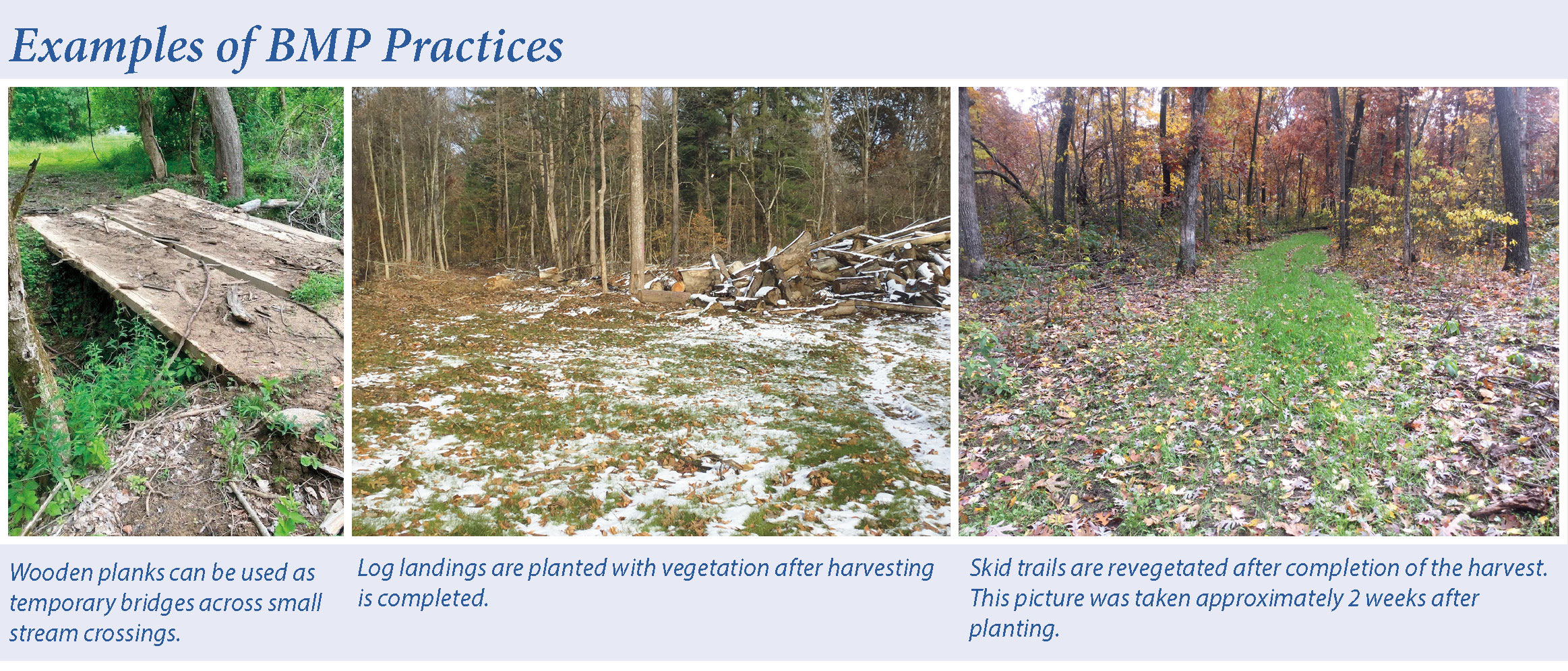

BMPs are guidelines because forestry is carried out in a highly variable and uncontrolled environment. When BMP practices cannot be placed as BMP guidelines suggest, it should warn us that we might need to do something to support these practices. An example of this is a skid trail being closed out on a 25% slope. The BMP Field Guide says that the waterbars (Figure 1) should be at a 30’-40’ spacing but terrain and residual trees near the trail force waterbars to be spaced further apart. When such areas occur, the person closing out the trail can look for alternative practices to help slow the water on that part of the trail, help get the water off the trail, or to stabilize the soil on that part of the trail. For instance, they could pull a top, or more than one top, to the trail and lay it across the trail at the same angle as a waterbar and lop them into pieces so that they lay flat on the ground. They could even seed and straw the area to help it stabilize the soil faster until a few leaf falls can armor that soil. Options are available when the tools commonly used will not do the job as intended.

On state forests, there has been an evolution in BMP standards and enforcement that landowners need not experience but can learn from. Two important tools in BMPs are the Field Guide and the monitoring form. You can liken the field guide to the subject being taught in school and the monitoring form as the test. However, this test can have some vague questions, such as asking if “perennial & large intermittent streams clear of obstructing logging debris.” The question itself is straight forward, but the term “large intermittent” can cause confusion.

We at the state grappled with that question for some time before we came up with a standard, which was in effect from July 1999 through July 2010, and said that all streams 4 feet wide or wider were classified as “large intermittent” streams, which required the foresters and the loggers to make sure such streams were clear of obstructing logging debris (Figure 2). All parties knew what the standard was for contractual purposes from beginning to end and could easily be identified on the ground.

Over time the state reviewed this standard and determined that an intermittent stream on a United States Geological Survey (USGS) map was a better standard to work from, would accomplish the goals of the program, and was obvious on every quadrangle map, so the standard was changed and was reflected on the contracts. However, no matter what kind of stream it is, all logging debris needs to be removed from streams that have a one square mile watershed or larger because the IN Flood Control Act includes tops in the definition of fill which is prohibited in that law. So, BMPs evolve over time in accordance with changes in laws and regular evaluation.

The foresters on the state properties will often work with the loggers to put in water diversions and other practices when they first start but will often let the loggers closeout harvest areas if they have worked with those loggers in the past and know how well they do the BMPs. However, the foresters will still look the sites over closely before releasing the contract. This also comes from years of experience of knowing what works and what does not on the soils and topography around that specific property. More than 20 years after implementing the BMP program on state forests, the result is a sustainable skidding and access trail system and not have to move them every time we have a harvest because the trails have washed out or hold water making them unusable. There are many examples of trails that were placed correctly on the landscape but were not used or closed out correctly and now another trail must be built which may not be placed well on the landscape, or they may reuse those bad trails even though they may increase the deterioration of that trails.

You might say that what the state is doing with BMPs is all fine and good, but what does it mean to private landowners in the state? The answer to this hypothetical question would be that the state has good data showing what might work for you, your woods, and the future of both.

BMPs can have a long-term impact on your property by minimizing impacts of the harvest and help it to provide recreation, resource protection, and other values. For instance, at a landowner BMP training rubber “water deflectors” were demonstrated because the owner of the site of the training had just put some in on the main trails throughout his property and were a great long-term tool but would not be an efficient tool for a logger to install on a hillside trail that will not be used until the next harvest (Figure 3). Examples of these are in place on some access roads in the Skyline area of Jackson-Washington State Forest. Many private stone driveways in IN could use these deflectors as well as main trails that are used more than just during a harvest. These deflectors divert water from the trail but allow equipment to drive over them without any “hump” for a truck or tractor to get over.

Duane McCoy is a professional forester who serves as the Timber Buyer Licensing Forester for the Indiana DNR Division of Forestry. Duane works on the Timber Buyers Licensing program, Indiana Forestry Best Management Practices (BMP) program, Watershed Conservation through Forestry program, and the Hoosier Ecosystem Experimental (HEE) Research Forest project. If you have any questions concerning forestry BMPs in Indiana please contact Duane McCoy at dmccoy@dnr.in.gov or Jennifer Sobecki at jesobecki@dnr.in.gov.