Bourbon – Kentucky’s Aged Spirit

Kentucky has recently made national headlines for increasingly rare and hard-to-find bottles of bourbon, mysterious whiskey heists and alleged shortages of white oak wood used to make barrels. All this attention has been good for bourbon distillers and the state’s economy. According to the Kentucky Distillers Association, production of bourbon has exceeded one million barrels annually for the past four years, reaching its highest peak since 1970. Record bourbon sales, expansion of bourbon production and a Kentucky bourbon tourism boom have helped the Bluegrass state recover from the economic recession of 2007.

Kentucky has recently made national headlines for increasingly rare and hard-to-find bottles of bourbon, mysterious whiskey heists and alleged shortages of white oak wood used to make barrels. All this attention has been good for bourbon distillers and the state’s economy. According to the Kentucky Distillers Association, production of bourbon has exceeded one million barrels annually for the past four years, reaching its highest peak since 1970. Record bourbon sales, expansion of bourbon production and a Kentucky bourbon tourism boom have helped the Bluegrass state recover from the economic recession of 2007.

It is the abundance of limestone spring water, high in calcium, that is credited with making Kentucky the premier location for producing aged spirits. The limestone soils and calcified water known for producing superior thoroughbred horses is also why Kentucky produces nearly 95 percent of all bourbon produced.

However, bourbon also benefits from generations of distilling expertise and a unique relationship with the American oak cask in which the spirt is aged. In fact, the freshly distilled whiskey, or “white dog,” is completely clear when it enters the barrel. It emerges as an amber liquid with flavors of caramel and butterscotch as a result of aging in the charred oak barrel for years.

As set forth in a resolution adopted by Congress on May 4, 1964, only whiskey produced in the United States and distilled to no more than 80 percent alcohol by volume (160 proof) from a fermented mash containing a minimum of 51 percent corn and entered into the barrel at not more than 62.5 percent alcohol by volume (125 proof) in charred, new oak containers may be rightfully labeled bourbon. Bourbon has no age requirement, but to be labeled straight bourbon it must be aged two years; in addition, any bourbon aged less than four years must include an age statement on the label.

The recent rise in popularity of bourbon is due to changes adopted by the industry over the past 25 years emphasizing high-quality, small-batch, single- barrel and premium products now commonly produced by the distillers. Back in the mid-1970s, bourbon was having a difficult time competing with the new popularity of wine and “white spirits” such as vodka. Consolidations and corporate takeovers of familyowned distilleries occurred, the emphasis on quality faded and some bourbon distilleries closed down. In the early 1990s, in an attempt to recover its former status among spirits, the bourbon industry updated its marketing strategies, developed premium offerings and incorporated tourism to sell the bourbon experience. However, it was a small, little known brand with a passion for quality that sparked a cult following.

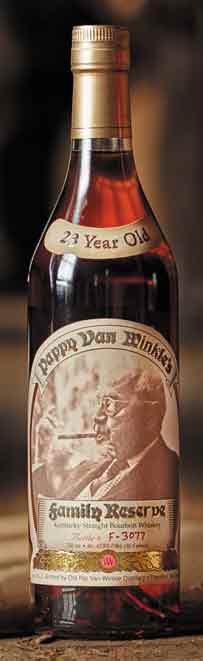

In 1992, the premium bourbon business had been depressed nearly 20 years when Julian Van Winkle III, the grandson of Julian “Pappy” Van Winkle, began releasing his 12 and 15-year-old bourbons under the Old Rip Van Winkle label. In 1995, Julian bottled the first 20-year-old bourbon and named it for his grandfather: Pappy Van Winkle’s Family Reserve. Of the five bourbons and one rye produced by the Van Winkles, the 20-year-old bourbon is considered the best. It has a rating of 99 out of 100, the highest rating ever given to a whiskey by the Beverage Tasting Institute at its World Spirits Championships. Today, a bottle of Pappy can’t be purchased at a local liquor store. Sales are limited to large liquor retailers, and the few bottles that arrive are sold by lottery or prearrangement. The Van Winkle Family entered into an agreement with Buffalo Trace to produce the Van Winkle bourbon and rye on May 1, 2002, in order to maintain the principles of the brand and ensure continued production.

By extending the aging period for premium bourbons, distillers are taking advantage of the unique relationship between whiskey and wood that improves the color, aroma and taste of the bourbon in your glass. All distillers agree that the white oak barrel – its construction, position in the warehouse and the amount of time the spirit spends in the barrel – most heavily influences the bourbon. White oak, Quercus alba, and Chinkapin oak, Quercus muehlenbergii, are the two species most commonly used in tight cooperage or the building of a whiskey barrel. The cells of these white oaks contain tyloses, which are outgrowths on parenchyma cells of the tree’s xylem. These cells “dam” up the vascular tissue and it is these clogged pores that prevent a white oak barrel from leaking.

The American White Oak Barrel

The coopering process begins when newly sawn staves are air dried for six months to one year. Some machining, heating and bending is required to fit the 31 to 33 staves into the rings that temporarily hold the barrel together as it is being built. Bourbon barrels are charred on the inside surface according to the distiller’s specification. The heat produced during the charring process creates a caramelized layer from the natural sugars present in the wood. These layers are responsible for bourbon’s reddish color and caramel and butterscotch flavors. The barrel is finished with hoops hammered into place and heads that seal the bottom and top of the cask. The bung hole is drilled and the barrel is checked for leaks by filling with water. The water-tight barrel is held together without nails, fasteners or glue. As the bourbon ages in the barrel it is absorbed and released into the oak with changes in temperature. The bourbon industry has experienced some growing pains as it has tried to expand its production capacity to meet the rising demand. Over the past several years, articles have begun appearing in The Wall Street Journal about a shortage of white oak for making whiskey barrels. Accounts of higher prices for American white oak barrels and claims of unfilled barrel orders have been reported.

The White Oak Supply Chain

As sales of bourbon, rye whiskey and Tennessee whiskey – all products that use new American white oak barrels – increased 35 percent from 2010 to 2014, there was a proportional increase in the demand for white oak stave logs. A stave log is a white oak log of sufficiently high quality to produce clear, fine-grained, quarter sawn planks, called staves, used to make 53 gallon barrels. Log buyers for veneer, stave and lumber logs all compete for a similar quality white oak log. Although the highest quality logs are used in hardwood face veneers and the lower quality logs are used in appearance grade lumber, there is some overlap that creates competition. Both the grade and price of these logs can vary as demand rises and falls.

White oak stave logs represent a small amount of the total timber harvested in any one timber sale. It is generally less than 10 percent on average in oak-hickory stands. In Kentucky, grade sawtimber used to manufacture appearance lumber for furniture, flooring and millwork still uses the lion’s share of the logs produced from the sale of hardwood timber. When housing starts crashed during the recession of 2007, there was virtually no market for 90 percent of the timber on a tract. In fact, hardwood lumber production was at a 50-year low. Although stave log prices remained high, timber was not being sold because overall markets didn’t justify the sale.

From 2010 to 2014, there was a significant increase in demand for all forest products. In the short-term, this out-paced the logging industry’s ability to respond and caused log price increases for most forest products until supply and demand returned to a balanced state. Cooperage plants and stave mills have upgraded equipment and added additional manufacturing capacity to increase production yields, reduce transportation expenses and minimize overall procurement costs. The shortages experienced are characteristic of adjustments to the supply chain structure for raw materials and less about a shortage of white oak trees.

The USDA Forest Service Forest Inventory and Analysis Unit has deemed white oak an extremely important resource in the forests of Kentucky. Not only does white oak have the greatest volume of all tree species within the state, Kentucky contains 14 percent of the entire white oak resource located within all Southern states. The large volume and large acreage of white oak present on private land makes white oak an extremely valuable forest resource, contributing significantly to the Kentucky economy. In fact, according to the 2015 Kentucky Forestry Economic Impact Report, published by the University of Kentucky Forestry Extension, Kentucky’s leading forest product export is white oak barrels, followed by lumber comprised mostly of white oak.

While current inventory numbers look encouraging, concern is developing about the declining quality of the white oak resource. The proportion of select white oak volume found in grade 1 logs has declined from 15 percent in 2004 to 10 percent in 2012, while the volume in belowgrade logs has increased the same amount, from 9 percent to 14 percent. From this data, foresters in the state are speculating that current logging practices and market conditions are encouraging exploitative logging practices which remove only the most valuable trees during the harvest and leave lower grade trees in the woods. Through landowner education efforts, state and extension foresters are encouraging landowners to consult with a professional forester before harvesting and invest in a forest management plan to improve long-term forest productivity.

Oak Shelterwood Used to Improve Oak Advanced Regeneration

Developing high quality oak forests requires the presence of well-developed oak seedlings and saplings in the forest prior to harvesting the mature timber. In oak dominated stands acorns germinate and oak root systems produce sprouts that are referred to as advanced reproduction. Because they are relatively shade-tolerant at this point in their lives, white oak seedlings and saplings can persist on the forest floor for long periods of time without developing the size or vigor required to become future crop trees. Oak stands on intermediate and high quality sites commonly have well-developed midstories comprised of shade-tolerant species such as sugar maple, American beech and red maple. These conditions lead to light levels on the forest floor that are not sufficient for the development of advanced oak reproduction. If the stand is harvested under these conditions, the small, under-developed oak seedlings and sprouts quickly become over-topped by the other species. By applying the oak shelterwood method and reducing the midstory competition, advanced oak reproduction grows and develops into high quality saplings capable of developing into crop trees.

Specific conditions must be present for this silvicultural practice to be successful. When conducting forest inventories for forest management plans, identify stands that are well suited to apply the oak shelterwood method.

To be a good candidate for this procedure, the stand’s site index should be intermediate to high, typically greater than 65 feet for upland oak at age 50. When site indices drop below 65 feet, oaks are capable of natural regeneration without assistance. The forest canopy should be comprised of dominant and codominant oaks and the stand should be within 10 to 15 years of maturity. In addition, oak seedlings must be present on the forest floor. A white oak forest will accumulate oak regeneration over time from acorn germination and root sprouting. This advanced reproduction will occur in patches and the seedlings and saplings will be present in different stages of development. If oak seedlings are not present in sufficient numbers, scarification to improve acorn germination prior to midstory removal is required. If oak reproduction is present in the stand with 50 to 100 stems per acre, four feet in height or greater, the stand already contains sufficient advanced oak reproduction and the oak shelterwood method is not required. Research is being conducted on supplementing natural reproduction with planted stock to improve the odds of successful regeneration when adequate natural reproduction can’t be obtained in time.

Assessing the condition of the oak seedlings prior to midstory removal is important and requires some practice. The vigor of the advanced oak reproduction describes the seedlings’ ability to respond quickly to release and is typically expressed in height, stem diameter and form of the seedling. If a bumper crop of acorns has generated a large number of seedlings that still have apical dominance, then the oak shelterwood method should be applied as soon as possible. If the number of oak seedlings is low or they are extremely small and have lost apical dominance, delay implementing the oak shelterwood practice until the number and vigor of seedlings improve. If germination fails after a mast crop is produced, consider soil scarification or burning the leaf litter. Scarification works best if it is implemented just after a bumper crop of acorns has fallen to the ground and before the leaves fall. Once adequate oak reproduction is present, implement the midstory removal.

The objective of the practice is to remove the competing midstory and understory to provide improved light conditions for advanced oak reproduction and build oak seedling vigor relative to the other competing vegetation. The desired condition is a filtered or diffuse light produced by a tall overstory canopy and few midstory stems that cast dense shade. Typically, this requires removal of approximately 20 percent of the stand’s basal area. Begin by treating the smallest stems that can be practically removed and then moving up to larger diameter stems. It is important to leave the dominant and codominant trees in place because too much light can cause negative outcomes. Concentrate on removing overtopped, suppressed and intermediate shade-tolerant trees. Always make the decision to remove trees based on how the absence of that tree will impact the type of light on the forest floor.

Using a herbicide is the most effective way to remove these trees. Cutting shadetolerant trees without using a herbicide will lead to sprouting and may create a greater shade problem. Also, herbicides ensure better control over competing vegetation by diminishing their seed banks over time. An injection application has been found to be the most effective and cost-efficient method of removal.

Triclopyr, a herbicide manufactured by Dow under the name of Garlon 3A or Element 3A, is a non-soil active product used in a one-to-one ratio in water and applied at a rate of one injection per one inch of tree diameter measured at DBH. The injection is commonly made with a machete or hatchet and the injection needs only to penetrate the bark and enter the actively growing cambium of the tree. Make the injections at a comfortable height and apply the herbicide to the open injection site. Garlon 3A and Element 3A both carry a label warning that the chemical can cause irreversible eye damage if it gets into the eyes. My preference is to use a machete and spray bottle to avoid chemical splash.

Imazepyr, a herbicide manufactured by BASF and sold under the name of Arsenal Applicators Concentrate (AC), is a foliar and soil active chemical that is absorbed by foliage and translocated into roots, preventing most resprouting. Use an application rate of one injection per three inches of tree diameter measured at DBH. The herbicide mixture for this application is 20 percent in water. Arsenal AC requires less total herbicide, allows faster application rates and the ability to reduce resprouting. Although applicators should always wear personal protective equipment (PPE) regardless of the herbicide applied, Arsenal does not have the same eye damage concerns. Arsenal must be used with care by experienced applicators because overapplication or spills will result in death or damage to non-target trees. Damage to dominant and codominant oak trees has occurred when strict adherence to application requirements was not followed.

Once the midstory competition is eliminated, the oak seedlings grow larger and their root systems gain strength. As the advanced oak reproduction obtains height growth of four to six feet, the large overstory trees are removed in a regeneration harvest. These oak seedlings are now free to grow and a new oak forest has been regenerated.

The Future Of The White Oak and

Bourbon Industry

Can Kentucky’s forests continue to meet the increasing demand for white oak products? Lately this has become a common topic of discussion whenever Kentucky foresters get together. State government, the distillery industry and the general public want to know what must be done so Kentucky doesn’t exhaust its supply of white oak timber. Although that is an unlikely outcome, this uncommon attention toward the forest products industry may not be all that bad. In fact, it is an opportunity to discuss forestry with a new audience that is suddenly interested in the subject.

Recent forest industry and forestry field tours have included state legislators, distillers and woodland owners with a new appreciation of forest management. The Brown-Forman Corporation is a leading manufacturer of both bourbon and Tennessee whiskey and the only bourbon distiller that makes its own barrels. In their Corporate Responsibility Report, Brown-Forman aims to protect the health of the forests they depend on, particularly the white oak resources used to make barrels in which their spirits are aged.

The interest isn’t all local, either. Kentucky is a leading exporter of both new and used white oak barrels to the world’s aged spirit industry. Two of the world’s most popular aged spirits, Scotch and Irish whiskey, require used bourbon barrels for aging. Recently, consulting forester Patrick Purser of Purser, Tarleton Russell Ltd. Conducted a fact-finding mission in Kentucky for his client, Irish Distillers, Pernod Ricard.

“Irish whiskey production has increased significantly in recent years, leading to concerns about the American white oak pipeline for used bourbon casks. A careful assessment of the American white oak forest resource is necessary to determine its long-term sustainability and to aid in developing solutions where needed,” said Purser. “Irish Distillers recognize their responsibility to minimize their environmental impact and are participating in an initiative to lead and contribute to a sustainable food and drink industry in Ireland.” Purser attended a white oak sustainability conference, met with a Kentucky barrel stave producer and toured non-industrial private woodlands whose owners are currently applying oak regeneration practices on their forestlands.

The rising popularity of aged-spirits worldwide has presented foresters an interesting opportunity to discuss forest management, white oak and solutions for long-term sustainability of forest products.

Chris Will, ACF, is President of Central Kentucky Forest Management, Inc. The company specializes in forest management plans, timber sales, timber appraisals, expert witness testimony and large scale forest inventories.

Editor’s Note: This article was reprinted with permission. It was originally published in the 2017 Consultant, the annual journal of the Association of Consulting Foresters.