Bats, Caves, and Forests

by Carroll Ritter

Many conservation efforts are included in management of our forest resources. Not only are we designing plans for silvicultural outcomes, but also for habitat and species of concern. Bats are one of these species.

One’s perception of bats depends primarily on early teaching by parents or other persons. Historically, bats have been regarded as frightening or harmful creatures to be eliminated.

Fortunately, many educators today are much more attuned to the important ecological benefits of bats and call for conservation efforts to protect them. The beneficial roles of bats are quite impressive, especially in maintaining balance of insects. The Nature Conservancy estimates that insect control provided by bats is valued at $23 billion to our state’s agricultural industry. Fluctuations in bat populations may also be a “canary in the coal mine” indicator of parallel environmental concerns that need addressed. Considering that the average Indiana bat’s mass is about 7 grams (.25 ounce), the amount of work done for such a small creature is phenomenal.

Our state species include the Indiana Bat (Myotis sodalis), the little brown bat (Myotis lucifugus), big brown bat (Eptesicus fuscus), gray bat (Myotis griscescens), northern long-eared bat (Myotis septentrionalis), and tri-colored bat (also called eastern pipistrelle, Pipistrellus subflavus). All are recognized as endangered except for the big brown bat. These six species were most often observed in caves that I have visited over the years. Other bats found occasionally and seasonally in the state are primarily migratory and are designated as special concern species.

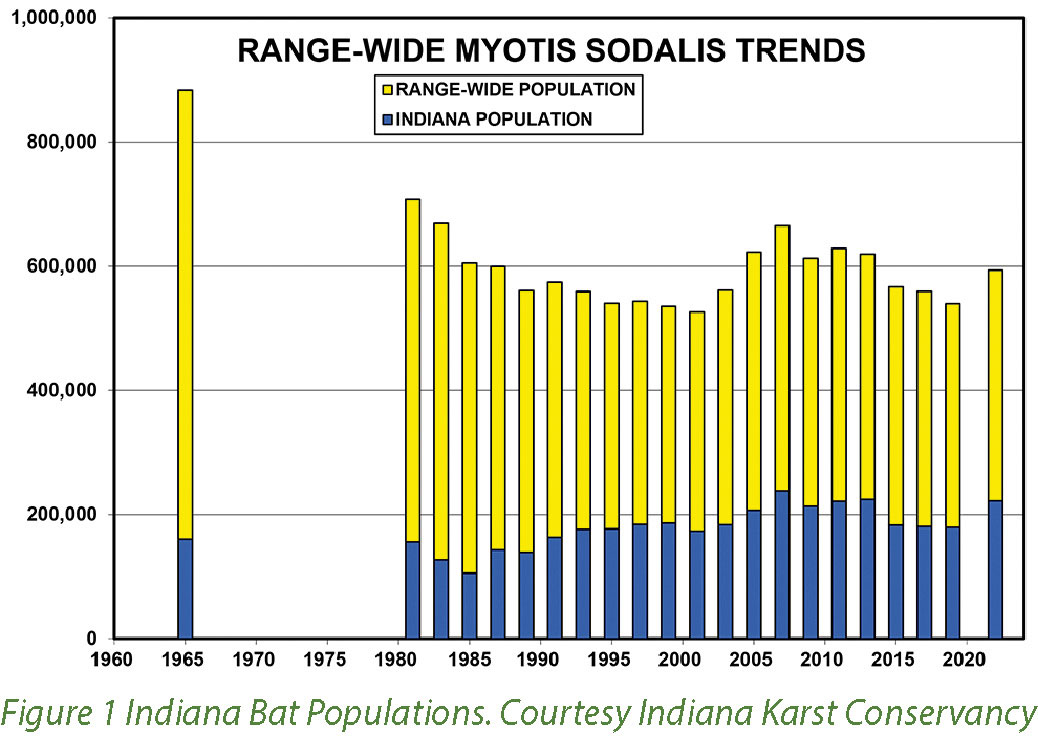

Although most of Indiana’s 3,000 caves provide potentially suitable winter habitat for smaller clusters, only about a dozen caves have sizeable winter populations. The long-running census on Indiana bats began in 1980 and the latest survey occurred in 2022. Conducted for the IDNR by Dr. Virgil Brack and Dr. Darwin Brack of Environmental Services and Solutions, their teams visit the selected caves and do most of the censusing by photography, quickly and efficiently, while minimizing any disturbance. I followed the same policy when exploring caves years ago.

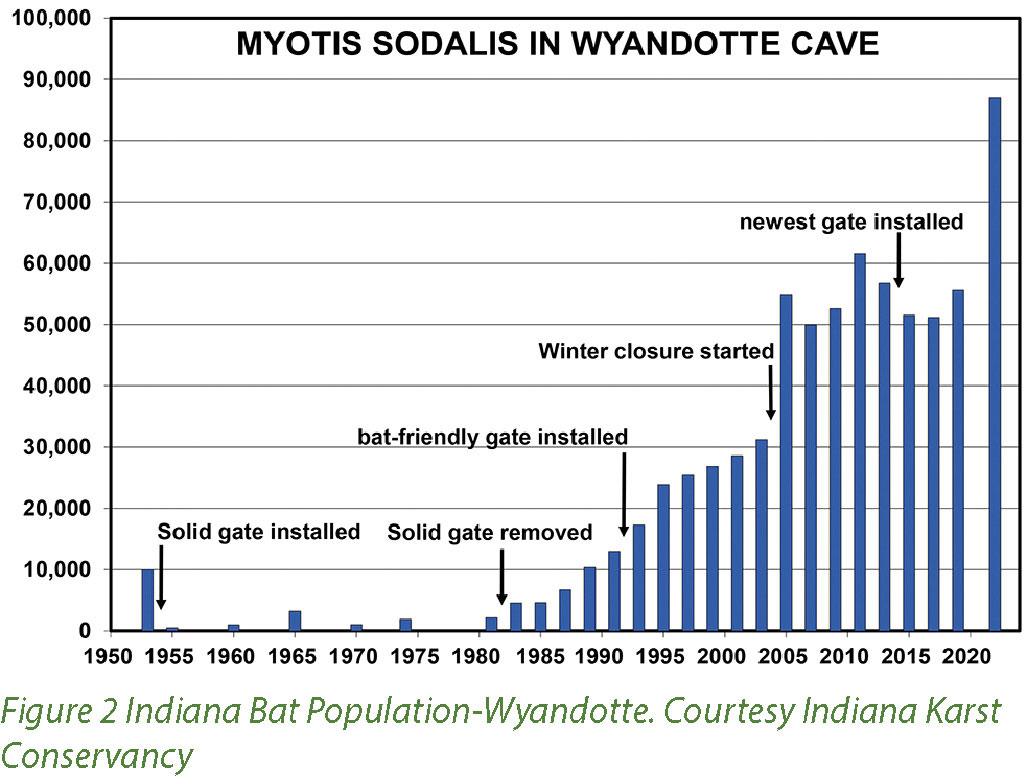

Trends show some encouragement from the devastating impact of white-nose syndrome, which arrived here in 2011 and drastically plunged the population of bats in general. Note from Figure 1 that the overall Myotis sodalis population has had its ups and downs over the years but the latest census shows some improvement. It also appears that preferred locations for their hibernacula have shifted toward the very southern tier of counties, especially Harrison and Crawford. Monroe and Greene had some of the largest wintering populations years ago, with one cave alone hosting some 77,000 bats. Wyandotte Cave is now the leading site, with a 2022 census of 87,000 Indiana bats. (See Figure 2). Other species are recorded if observed. The little brown bat continues to struggle with any rebound from the white-nose syndrome impact.

What has affected bat populations? As with many species, delays in proactive recognition, study, and policy wait until the problems have become substantial. The Endangered Species Act has helped immensely and even today recognizes more needed listings. Our primary concern has been and is, loss of habitat. That same bat area is also home for other plants and animals which benefit from wise stewardship decisions. Years ago, bats hanging from the ceiling may have slept over bears hibernating for the winter. Bear wallows have been documented by cavers as they mapped passageways. I once encountered a baby fox on a ledge resting while the mother was outside looking for the next meal. I quickly retreated. It is not uncommon to see raccoon tracks in caves and most likely coyotes now den up in some of the sandstone caves and overhangs in my area.

The forest environment provides many opportunities for bat conservation strategies, especially since several factors are most likely present. Retention of snags, maintaining the presence of hickory and other summer maternity trees, open flyway corridors, and water holes all contribute essential components of favorable habitat. We must realize that bats need that summer hibernaculum as well as that cave in the winter. Those old shagbarks, shellbarks, oaks, and maples are where the mother hides her young while foraging. If the woods contain the components listed above, you are on the path to maintaining suitable habitat. Lastly, those caves and sinkholes provide a wintering home. Whether large cave openings or small cracks and crevices, consider protecting them as well. Our tendency to fill these openings has effects on creatures who may live there.

While a cave certainly feels warmer than the outside in the winter, be aware that your exploring needs done with care or postponed if any sleeping bats are encountered. Disturbance may mean arousal, consumption of body fat, and inability to fly out and feed.

Precautions have been very strict during the white-nose syndrome times, with cave closures common on state and federal properties. Some permitting is now available. Finally, always get permission from private landowners. As always, take only pictures and leave no trace or impact on this fragile environment and our great bat friends.

Special recognition to the Indiana Department of Natural Resources Nongame Wildlife Fund, the Nature Conservancy, and the Indiana Karst Conservancy.

Carroll Ritter is a retired science teacher and naturalist educator.